The hinge of change was news that Grandfather Edwin had suddenly died with the éclat of the “Man of the world” that Aunt Bea so admired. He had felt sleepy after lunch, went upstairs to lie down and a stroke killed him as he took off his shoes. I had not known him and he had obviously decided, many decades ago, that his daughter and her family were surplus to his life. His easy death seemed to merit appreciation rather than mourning.

My household adults also seemed only mildly to regret loss of someone they hardly knew. His departure solved problems. Carlops was wonderful for children: a stream-full of sticklebacks and tiny trout marked the garden end and beyond this was a rabbit valley with drumlins, caves, peewits, curlews and assertive ravens. For adults this was only bleak wilderness with no fantasy-opportunities.

I had grown happier at Heriot’s than I had been anywhere else and made more interesting friends than I had ever known but my adults had no relish or optimism for life in Scotland. Ivy and Claude were as pleasant and unobtrusive as insecure dependence on my father’s pension and temperament allowed. Dad grew increasingly depressed that Edinburgh offered him no opportunities for fantasy careers, such as “importing and exporting machine tools”; he had no capital, contacts, or business experience.

In India Dad had been the boss of large offices controlling large Police Districts, with an additional part-time role as the pivot of our small family. He seemed to lack interest in most humans, but never affection for us. He just could not communicate warm feelings through everyday chatter but needed to make passionate declarations in long vehement monologues that suppressed general conversation. Ivy, Claude and Kenneth were as tactful as dependent humans can be but were oppressed by his eloquent despair, did not share his frustrated entitlement and accepted that their lives in Britain must be hard times stoically endured. They wanted to move to Edinburgh City where Claude and Kenneth could find factory jobs. The chance to fill Edwin’s space in Aunt Bea’s house was a welcome escape and a boost to Dad’s dreams of new beginnings. My delight in curlews and lapwings, admiration of dignified grey Edinburgh and discovery of the best friends I had yet known did not matter. At least I could begin to feel less guilty that I was becoming much happier than my adults and failing to find any way to share my new pleasure in life with them.

We re-discovered the Rochester house and the snug outdoor lavatory, the shed, full of interesting tools and dried pots of paint and the tangled grass patch where Benjamin was buried. Old Mum moved into Edwin’s ex-room on a level with an adjoining bath and washing room that also had the only wall-mirror in the house. Her weight and the stairs meant that for her last 5 years she rarely left this room, and never moved beyond this level of the house or saw the street outside. Mum and Sheila had the front top bedroom and Dad and I shared the top back. Aunt Bea went into the ground-floor front room, once her parlour, sleeping under a blotchy picture of a lively eighteenth century cavalry-battle painted by her late husband, Tom. He had made a good living as a painter and decorator and his artwork suggested that, had he survived, he might have become notable for pub-signs.

I warmed to the late Edwin when I discovered a trunk in the cellar that he had filled with the collected works of H.G. Wells. The War of the Worlds and Mr Polly saw me through initial confusions and anxieties in Rochester. My parents found no Catholic School but their apprehensions were mollified by discovering that I could be taught, free, in the local free Grammar School.

I was now in good shape to relish this huge luck. My Heriot friends had sharpened up my British Act and I even had a slight Scots accent, ( e.g. pronouncing “Maths” as “Maarths”) and was teased for this rather than for exotic biology. Some anxious uncertainties as to how to become more British had disappeared. Rationing and my mother’s cooking had reduced me to average shape for my age and I was discovering that school-teachers were not just cosplaying bouncers programmed to control entry into a club run by a temperamental God; only bigger, smarter, well-intentioned humans.

Distance from the nearest Roman Church meant that we grew lax in attending Mass or Confession and my parents’ public Catholicism attenuated into solitary pleading for favours from their God. They would have, truthfully, insisted that their love for each other and also for my sister and myself, was great (and part of the duty they they owed to HIM). Unfortunately love is not effectively communicated by repetitious, vehement declarations. It is a control program that generates small kindnesses and pleasant interactions.

School was a marvellous escape from home. The syllabus was undemanding and my teachers’ enthusiasm intermittently glinted through their tired tolerance. Most had recently de-mobbed from WW2 service and memories of this, the most vivid part of their lives, overwhelmed their every-days in dingy post-war Britain. Our geography- master, Mr Hadlow, found it more interesting to explain exactly why it is difficult to drive a truck to keep up with others in a long military convoy than to discuss volcanoes and Ox-bow lakes. I was excused (i.e. excluded from) Latin and French because I was so incompetent that I could not hope to pass impending O-level exams in them.

I made excellent new friends and, even better, discovered the Rochester Public Library which had more books than I had ever seen in one place. Marvellously I could take away any three at a time for free. There was also a kind librarian called Esme with whom I fell in love. School was not just an escape from my family but a training ground for tiny new ambitions and achievements. I passed GCSE O-levels and joined a sixth form to prepare for A-levels. Rochester became a friendly environment and my ease in the pleasant city, and increasing independence and self-confidence contrasted with the bad times my adults were having.

At home I spent most of my time in the second-floor back bedroom that I shared with my father, avoiding the rest of my family and inventing strange ways to mitigate boredom. The most rewarding was to look through a pair of old binoculars at the neon street-lights that trailed up my horizon of Chatham Hill. If you waggle binocular lenses distant neon lamps trace ribbon-smears of their light across your retinas. This is not remarkable - but because neon lights are not constant, but flicker, fast, moving lenses paint on your retinae light ribbons broken by narrow, precisely-spaced, strips of shade. I was intrigued to work out that this happens because we see neon light as un-interrupted glow but rapid lens movements stretch both the light pulses and the otherwise imperceptible off-instants across our retinas. This is hardly the kernel of a theory of relativity but stretching light and time across your eyes gives some relief from boredom by illustrating that the world is not at all what our sense-organs fool us that it is. My other anti-boredom experiments on my conscious perception were sniffing a household cleaning fluid called Thawpit until my vision dimmed and I heard, and felt, a buzzing in my ears and head. Even sillier was testing my understanding of the role of carotid arteries by looping a cord around my neck tied to the support-rail for clothes-hangers in a wardrobe. After brief forward-kneeling-leaning, dizziness confirmed interrupted blood supply to my brain. These ways of distorting consciousness were much duller than those that 1970 Hippies were to discover but as good as most available to schoolboys in the early 1950’s

My new school-friends were a great pleasure and we used to meet in their family living rooms to talk pretentious nonsense, discover Eartha Kitt’s amazing vocal range and mildly suggestive lyrics (Let’s Do it) and hear the first of amazing Tom Lehrer. On exceptional evenings we would drink a very little cider. It was awkward that I could never repay these fine evenings in my own home because my father turned all visiting friends away at our front door. This was not just ill nature but practicality. Blanche, the browner of my mother’s lifelong friends the two Bell sisters, (her startlingly white sister was harsh Aileen) had come to the UK and lodged with us while she took a course in how to work a Comptometer, a very early electric calculating machine. Blanche was a cheerful addition to our morose household but her presence meant that there was never any room free for us to use. My friends were puzzled and curious but never understood. They did not say so at the time but they were also quite offended. Fifty-five years later one of them wrote from the Hague, where he had been a Professor of International Politics, to scold me into explanations that I found too difficult when I was 15.

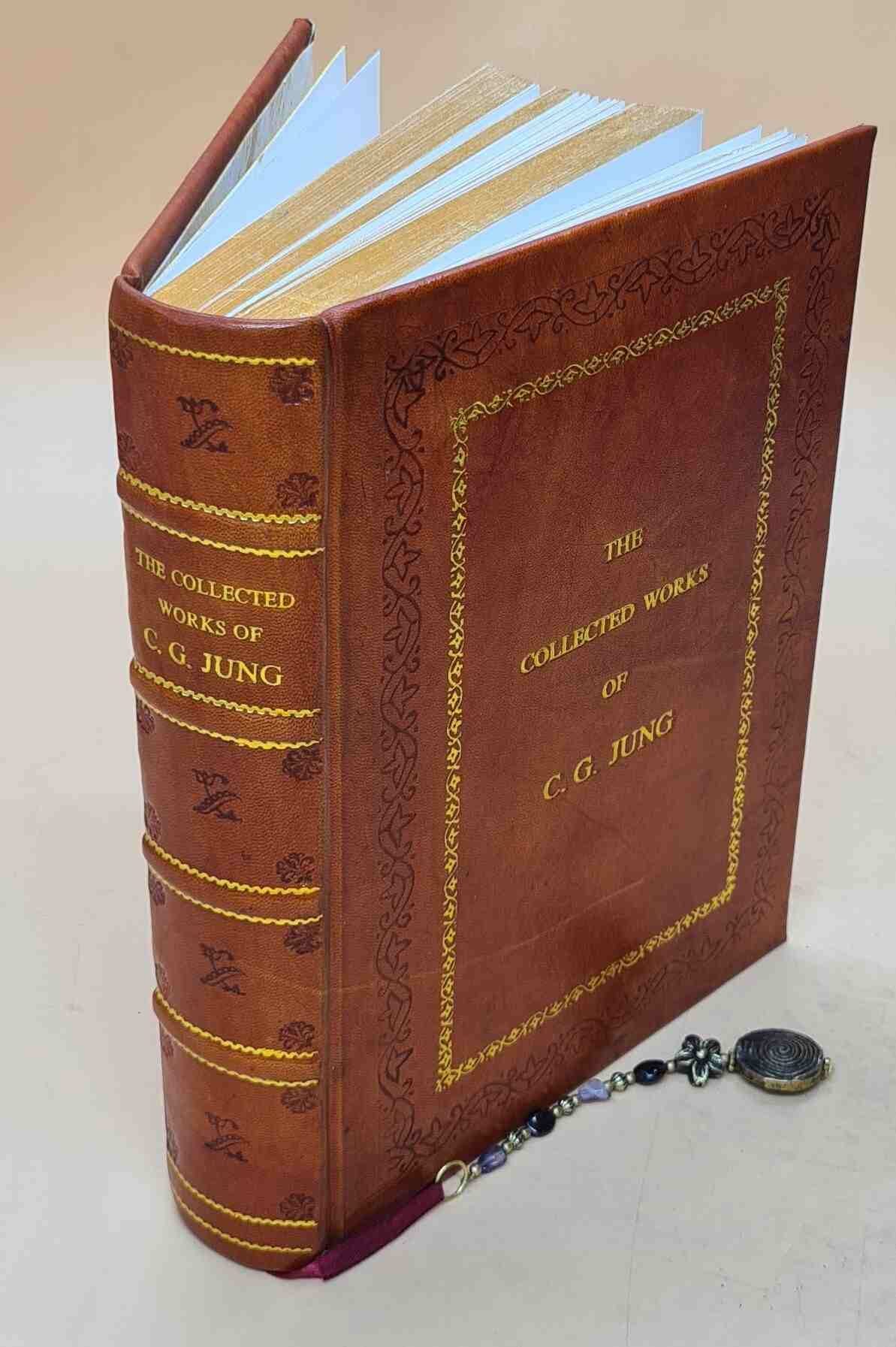

My life changed in other ways. I found an evening job, in the Rochester Casino roller-skating rink that relieved me from needing pocket money from my parents and gave me a reason to be away from home most evenings. Handing out and taking back roller skates was not a vivid social life but I tried to advertise myself as an intellectual-girl-magnet by taking from the library a huge bound copy of The Collected Works of Carl Jung that Esme allowed me to keep for longer than the library-legal fortnight. I displayed this on my roller-skate-issue-counter and, occasionally, ostentatiously read it to signal extreme intellectualism. No-one ever commented. This was just as well because I could not have sustained discussion. I did not get on with Jung. His ideas seemed pretentious and silly and of no help with meeting girls.

Rochester has a fine Norman Castle keep, with some anecdotes of minor sieges. It is also in a part of England in which tales of battles of Saxons and “Yeomen of Kent” against Vikings and Norman invaders are legends in which some schoolboys, hyper-romanticised by random reading, still imagine roles. I became enthralled by spurious and genuine discoveries of my new life and world. The only blemish on my new happiness was growing distance from Dad.

Britain had crumbled his authority and was altering the entire family dynamic. In happy families mutual affection is learned and communicated through banter and affectionate teasing that Dad could never understand or manage. He tried to communicate his immense attachment to us by sudden, strenuous outbursts of love and need, grasping my sister Sheila and me, each with one huge arm, squashing us to his chest and repeatedly declaiming that he would “Give his right arm for us”. I was sure that this was literally true, at least at that moment, but puzzled what use the huge limb clutching my shoulders could be if it were amputated and left lying about the house or who might want it in exchange for us. The only response I could make was to simulate complacence with whatever it was that I was being offered by lying passive against his huge chest.

Even in India Dad had colleagues, but had never seemed to like them much or to have easy friendships outside the family. Perhaps this was why his only idea of conversation was to deliver endless, clever and witty monologues that he obviously thought made him as companionably entertaining as anybody could possibly be. His favourite TV experience was an advertisement for Apple Cider that showed a crowded bar full of people having a noisy happy time. Obviously his ideal world would be raucous with merry congeniality - but I could not see how he could manage this. Perhaps he saw a role as a respected and much-loved senior friend entrancing his doting companions with long, brilliant, solo performances. He would have agreed that conversation needs reciprocity but had never learned this trick and would have suspected disrespect if offered cheerful banter. Perhaps the cider advertisement was another hint as to what life in Britain might be if only he could somehow crack the code. My sister and I were the only tiny group that he could still dominate and, in his way, deeply love but Rochester was giving us lives of our own and interests that he could not share and this made us increasingly distant from him. In contrast to our newly developing lives he had nothing to fill his time except fantasy escapes from his new, pawky reality. His life-task and ambitions shrank to “doing the football pools” and he prayed, both directly to his Catholic God, and to Mary, God’s softer-hearted Mum, to negotiate with her Son for his redemption by a brilliant prize. He began to report dreams of affable meetings with members of the British Royal Family. These did cheer him up a bit because he hoped that they might be omens of some sudden, happy transformation of his life.

Old Mum became ever more startlingly obese; cardiac problems swelled her feet and ankles and, as stairs became impossible she became imprisoned in her bedroom with nothing whatever to do. She never read a book or listened to the radio, or had TV or any company except my father. She grew increasingly feeble. Her room was on the same level as a bathroom extension that led to another in which Dad sat all day at a round table, endlessly striving for salvation by football pools. The bathroom had a tub, a washbasin with a spotty mirror and a pair of enamelled buckets. Old Mum, and also Dad, seemed to spend much time at the mirror inspecting their faces for signs of progressive decay. Old Mum would discover plump white sebaceous pimples, particularly on her eyelids. Her arthritic fingers could not squeeze them so she would corner me to do this. She would eat meals prepared for her together with Dad but had no other occupation. For my mother, and for silent, kind, scuttling Aunt Bea, it became essential to avoid uncomfortable interactions and they shared silences in the basement room.

Thawpit! That's carbon tetrachloride, so it's a mercy you were not relieving your boredom by sniffing AND smoking. You might have blown yourself up! I am feeing increasingly sorry for the grown ups, now. You must have been a kind, protective 15-year-old, and I love your "my adults".

Caroline (another Tom Lehrer fan at the same age)

https://c8.alamy.com/comp/D890EP/1928-advert-for-the-thawpit-home-dry-cleaner-intended-for-cleaning-D890EP.jpg

https://c8.alamy.com/comp/KRC24J/1940s-old-vintage-original-advert-advertising-thawpit-for-cleaning-KRC24J.jpg